_Orality and Literacy :

The Technologizing of the Word_

by

Walter J. Ong

( c. 01982 )

( the orality of language )

". . .it would be well to set the stage here by asking why the scholarly world had to reawaken to the oral character of language. It would seem inescapably obvious that language is an oral phenomenon. Human beings communicate in countless ways, making use of all their senses, touch, taste, smell, and especially sight, as well as hearing. Some non-oral communication is exceeding rich -- gesture, for example. Yet in a deep sense, language, articulated sound, is paramount. Not only communication, but thought itself relates in an altogether special way to sound. We have heard it said that one picture is worth a thousand words. Yet, if that statement is true, why does it have to be saying ? Because a picture is worth a thousand words only under special conditions -- which commonly include a context of words in which the picture is set.

Wherever human beings exist they have a language, and in every instance a language that exists basically as a spoken and heard, in the world of sound. Despite the richness of gesture, elaborated sign languages are substitutes for speech and dependent on oral speech systems, even when used by the congenitally deaf. Indeed, language is so overwhelmingly oral that of all the many thousands of languages --possibly tens of thousands-- spoken in the course of human history only around 106 have ever been committed to writing to a degree sufficient to have produced literature, and most have never been written at all. Of the some 300 languages spoken that exists today only some 78 have a literature. There is as yet no way to calculate how many languages have disappeared or been transmuted into other languages before writing came along. Even now hundreds of languages in active use are never written at all : no one has worked out an effective way to write them. The basic orality of language is permanent. . . "

( the modern discovery of primary oral cultures )

" . . .Havelock's _Preface to Plato_ (01963) extended Parry's and Lord's findings about orality in oral epic narrative out into the whole of ancient oral Greek culture and has shown convincingly how the beginnings of Greek philosophy were tied in with the restructuring of thought brought about by writing. Plato's exclusion of poets from his Republic was in fact Plato's rejection of the pristine aggregative, paratactic, oral-style thinking perpetuated by Homer in favor of the keen analysis or dissection of the world and of thought itself made possible by the interiorization of the alphabet in the Greek psyche. In _Origins of Western Literacy_ (01976), Havelock attributes the ascendancy of Greek analytic thought to the Greek's introduction of vowels into the alphabet, The original alphabet, invented by Semitic peoples, had consisted only of consonants and some semivowels. In introducing vowels, the Greeks reached a new level of abstract, analytic, visual coding of the elusive world of sound. This achievement presaged and implemented their later abstract intellectual achievements. . . "

". . .Anthropologists have gone more directly into the matter of orality. . .convincingly showing how shifts hitherto labeled as shifts from magic to science, or from the so-called 'prelogical' to the more 'rational' state of consciousness, or from Levi-Strauss's 'savage' mind to domesticated thought, can be more economically and cogently explained as shifts from orality to various stages of literacy. . .many of the contrasts often made between 'western' and other views seem reducible to contrasts between deeply interiorized literacy and more or less residually oral states of consciousness. The late Marshall McLuhan's well-known work has also made much of the ear-eye, oral-textual contrasts, calling attention to James Joyce's precociously acute awareness of ear-eye polarities and relating to such polarities a great amount of otherwise quite disparate scholarly work brought together by McLuhan's vast eclectic learning and his startling insights. McLuhan attracted the attention not only of scholars but also of people working in the mass media, of business leaders, and of the generally informed public, largely because of fascination with his many gnomic or oracular pronouncements, too glib from some readers but often deeply perceptive. These he called 'probes'. He generally moved rapidly from one 'probe' to another, seldom if ever undertaking any thorough explanation of a 'linear' (that is, analytic) sort. His cardinal gnomic saying, 'The medium is the message', registered his acute awareness of the importance of the shift from orality through literacy and print to electronic media. Few people have had so stimulating effect as Marshall McLuhan on so many diverse minds, including those who disagreed with him or believed they did. . . "

( some psychodynamics of orality )

" . . .Fully literate persons can only with great difficulty imagine what a primary oral culture is like, that is, a culture with no knowledge whatsoever of writing or even of the possibility of writing. Try to imagine a culture where no one has ever 'looked up' anything. In a primary oral culture, the expression 'to look up something' is an empty phrase : it would have no conceivable meaning. Without writing, words as such have no visual presence, even when the objects they represent are visual. They are sounds. You might 'call' them back-- 'recall' them. But there is nowhere to 'look' for them. They have no focus and no trace (a visual metaphor, showing dependency on writing), not even a trajectory. They are occurrences, events.

To learn what a primary oral culture is and what the nature of our problem is regarding such a culture, it helps first to reflect on the nature of sound itself as sound. All sensation takes place in time, but sound has a special relationship to time unlike that of the other fields that register in human sensation. Sound exists only when it is going out of existence. It is not simply perishable but essentially evanescent, and it is sensed as evanescent. When I pronounce the word 'permanence', by the time I get to the '-nence', the 'perma-' is gone, and has to be gone.

There is no way to stop sound and have sound. I can stop a moving picture camera and hold one frame fixed on the screen. If I stop the movement of sound, I have nothing-- only silence, no sound at all. All sensation takes place in time, but no other sensory field totally resists a holding action, stabilization, in quite this way. Vision can register motion, but it can also register immobility. Indeed, it favors immobility, for to examine something closely by vision, we prefer to have it quiet. We often reduce motion to a series of still shots the better to see what motion is. There is no equivalent of a still shot for sound. An oscillogram is silent. It lies outside the sound world. . . “

” . . .The fact that oral peoples commonly and in all likelihood universally consider words to have magical potency is clearly tied in, at least unconsciously, with their sense of the word as necessarily spoken, sounded, and hence power-driven. Deeply typographic folk forget to think of words as primarily oral, as events, and hence as necessarily powered : for them, words tend rather to be assimilated to things, 'out there' on a flat surface. Such 'things' are not so readily associated with magic, for they are not actions, but are in a radical sense dead, though subject to dynamic resurrection.

Oral peoples commonly think of names (one kind of words) as conveying power over things. Explanations of Adam's naming of the animals in Genesis 2 : 20 usually call condescending attention to this presumably quaint archaic belief. Such a belief is in fact far less quaint than it seems to unreflective chirographic (((written))) and typographic (((print))) folk. First of all, names do give human beings power over what they name : without learning a vast store of names, one is simply powerless to understand, for example, chemistry and to practice chemical engineering. Secondly, chirographic and typographic folk tend to think of names as labels, written or printed tags imaginatively affixed to an object named. Oral folk have no sense of a name as a tag, for they have no idea of a name as something that can be seen. Written or printed representations of words can be labels ; real, spoken words cannot be. . . "

" . . .In an oral culture, to think through something in non-formulaic, non-patterned, non-mnemonic terms, even if it were possible, would be a waste of time, for such thought, once worked through, could never be recovered with any effectiveness, as it could be with the aid of writing. It would not be abiding knowledge but simply a passing thought, however complex. Heavy patterning and communal fixed formulas in oral cultures serve some purposes of writing in chirographic cultures, but in doing so they of course determine the kind of thinking that can be done, the way experience is intellectualized mnemonically. . .

. . .Of course, all expression and all thought is to a degree formulaic in the sense that every word is a kind of formula, a fixed way of processing the data of experience, determining the way experience and reflection are intellectually organized, and acting as a mnemonic device of sorts. Putting experience into any words (which means transforming it a little bit-- not the same as falsifying it) can implement its recall. "

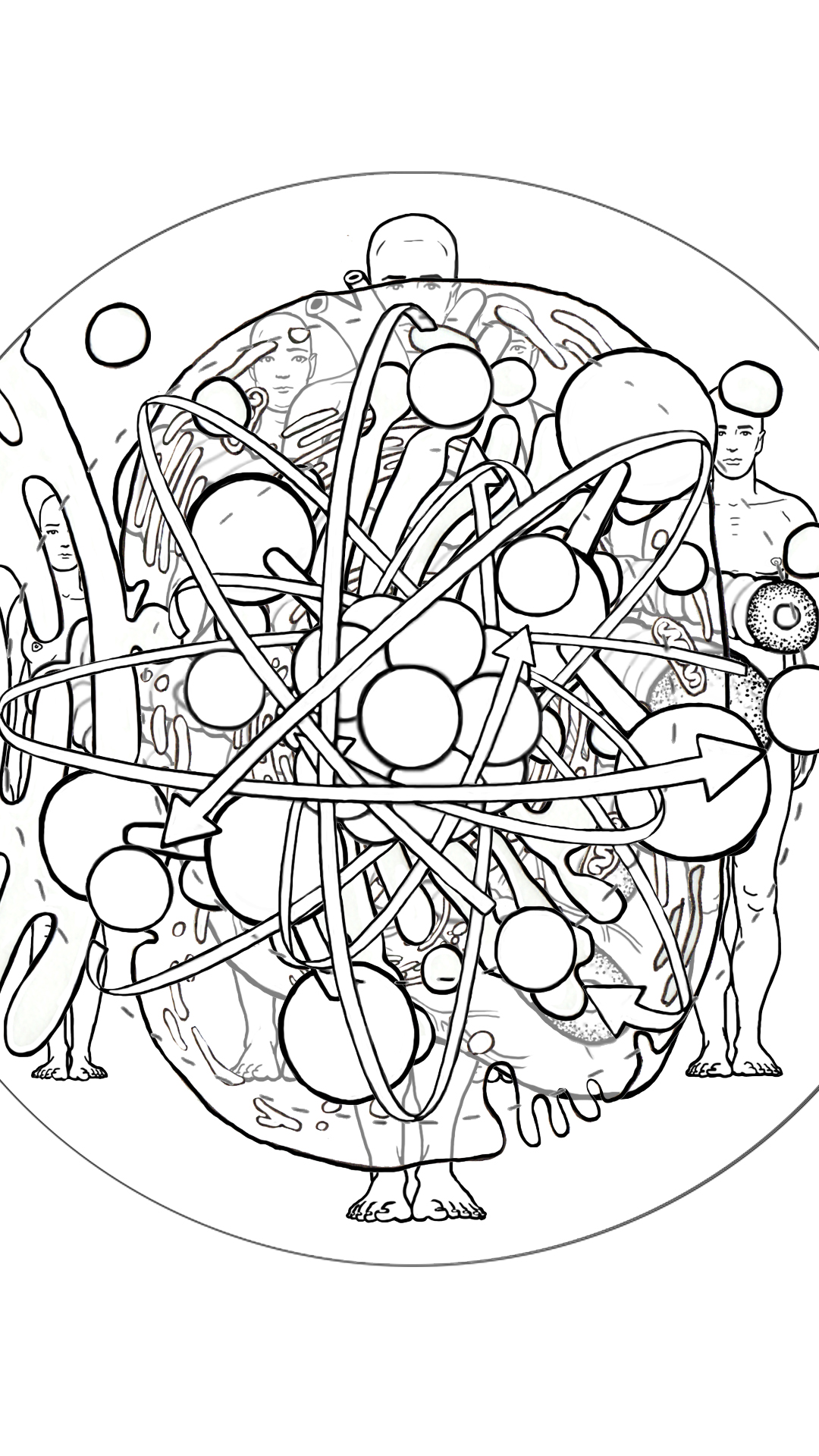

" Thought requires some sort of continuity. Writing establishes in the text a 'line' of continuity outside the mind. If distraction confuses or obliterates from the mind the context out of which emerges material I am now reading, the context can be retrieved by glancing back over the text selectively. Backlooping can be entirely occasional, purely ad hoc. The mind concentrates its own energies on moving ahead because what it backloops into lies quiescent outside itself, always available piecemeal on the inscribed page. In oral discourse, the situation is different. There is nothing to backloop into outside the mind, for the oral utterance has vanished as soon as it is uttered. Hence the mind must move ahead more slowly, keeping close to the focus of attention much of what it has already dealt with. Redundancy, repetition of the just-said, keeps both speaker and hearer surely on track.

Since redundancy characterizes oral thought and speech, it is in a profound sense more natural to thought and speech than is sparse linearity. Sparsely linear or analytic thought and speech is an artificial creation, structured by the technology of writing. Eliminating redundancy on a significant scale demands a time-obviating technology, writing, which imposes some kind of strain on the psyche in preventing expression from falling into its more natural patterns. The psyche can manage the strain in part because handwriting is physically such a slow process-- typically about one-tenth of the speed of oral speech. With writing, the mind is forced into a slowed-down pattern that affords it the opportunity to interfere with and reorganize its more normal, redundant processes. . . "

" . . .Redundancy is also favored by the physical conditions of oral expression before a large audience, where redundancy is in fact more marked than in most face-to-face conversation. Not everyone in a large audience understands every word a speaker utters, if only because of acoustical problems. It is advantageous for the speaker to say the same thing, or equivalently the same thing, two or three times. If you miss the 'not only...' you can supply it by inference from the 'but also...'

. . .

The public speaker's need to keep going while he is running through his mind what to say next also encourages redundancy. In oral delivery, though a pause may be more effective, hesitation is always disabling. Hence it is better to repeat something, artfully if possible, rather than simply to stop speaking while fishing for the next idea. Oral cultures encourage fluency, fulsomeness, volubility. Rhetoricians were to call this *copia*. They continued to encourage it, by a kind of oversight, when they had modulated rhetoric from an art of public speaking to an art of writing. Early written texts, through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, are often bloated with 'amplification', annoyingly redundant by modern standards. Concern with *copia* remains intense in western culture so long as the culture sustains massive oral residue-- which is roughly until the age of Romanticism or even beyond. . . "

" . . . All conceptual thinking is to a degree abstract. So 'concrete' a term as 'tree' does not refer simply to a singular 'concrete' tree but is an abstraction, drawn out of, away from, individual, sensible actuality ; it refers to a concept which is neither this tree nor that tree but can apply to any tree. Each individual object that we style a tree is truly 'concrete', simply itself, not 'abstract' at all, but the term we apply to the individual object is in itself abstract. Nevertheless, if all conceptual thinking is thus to some degree abstract, some uses of concepts are more abstract than other uses.

Oral cultures tend to use concepts in situational, operational frames of reference that are minimally abstract in the sense that they remain close to the living human lifeworld. . .

. . .Illiterate (oral) subjects identified geometrical figures by assigning them the names of objects, never abstractly as circles, squares, etc. A circle would be called a plate, sieve, bucket, watch, or moon ; a square would be called a mirror, door, house, drying-board. They identified the designs as representations of real things they knew. They never dealt with abstract circles or squares but rather with concrete objects. Teachers' school students, on the other hand, moderately literate, identified geometrical figures by categorical geometric names : circles, squares, triangles, and so on. They had been trained to give school-room answers, not real-life responses. . . "

" . . .although singers are aware that two different singers never sing the same song exactly alike, nevertheless a singer will protest that he can do his own version of a song line for line and word for word any time, and indeed, 'just the same twenty years from now'. When, however, their purposed verbatim renditions are recorded and compared, they turn out to be never the same, though the songs are recognizable versions of the same story. 'Word for word and line for line' is simply an emphatic way of saying 'like'. 'Line' is obviously a text-based concept, and even the concept of a 'word' as a discrete entity apart from the flow of speech seems somewhat text-based. An entirely oral language which has a term for speech in general, or for a rhythmic unit of a song, or for an utterance, or for a theme, may have no ready term for a 'word' as an isolated item, a 'bit' of speech, as in, 'The last sentence here consists of twenty-six words'. Or does it ? Maybe there are twenty-eight. If you cannot write, is 'text-based' one word or two ? The sense of individual words as significantly discrete items is fostered by writing, which, here as elsewhere, is diaeretic, separative. (Early manuscripts tend not to separate words clearly from each other, but to run them together.) "

" . . .oral memorization is subject to variation from direct social pressures. Narrators narrate what audiences call for or will tolerate. When the market for a printed book declines, the presses stop rolling but thousands of copies may remain. When the market for an oral genealogy disappears, so does the genealogy itself, utterly. As noted earlier, the genealogies of winners tend to survive (and to be improved), those of the losers tend to vanish (or to be recast). Interaction with living audiences can actively interfere with verbal stability : audience expectations can help fix themes and formulas. I had such expectations forced on me recently by a niece of mine, still a tiny child young enough to preserve a clearly oral mindset. I was telling her the story of "The Three Little Pigs" : 'He huffed and puffed, and he huffed and puffed, and he huffed and puffed.' My niece bridled at the formula I used. She knew the story, and my formula was not what she expected. 'He huffed and puffed, and he *puffed and huffed*, and he huffed and puffed', she pouted. I reworded the narrative, complying with audience demand for what had been said before, as other oral narrators have often done. "

". . .oral memory differs significantly from textual memory in that oral memory has a high somatic component. . .'from all over the world and from all periods of time traditional compositions have been associated with hand activity. The aborigines of Australia and other areas often make string figures together with their songs. Other peoples manipulate beads on strings. Most descriptions of bards include stringed instruments or drums'. To these instances one can add other examples of hand activity, such as gesturing, often elaborate and stylized, and other bodily activities such as rocking back and forth or dancing. The Talmud, although a text, is still vocalized by highly oral Orthodox Jews in Israel with a forward-and-backward rocking of the torso.

The oral word, as we have noted, never exists in a simply verbal context, as a written word does. Spoken words are always modifications of a total, existential situation, which always engages the body. Bodily activity beyond mere vocalization is not adventitious or contrived in oral communication, but is natural and even inevitable. In oral verbalization, particularly public verbalization, absolute motionlessness is itself a powerful gesture. "

" Primary orality fosters personality structure that in certain ways are more communal and externalized, and less introspective than those common among literates. Oral communication unites people in groups. Writing and reading are solitary activities that throw the psyche back on itself. A teacher speaking to a class which he feels and which feels itself as a close-knit group, finds that if the class is asked to pick up its textbooks and read a given passage, the unity of the group vanishes as each person enters their private lifeworld. An example of the contrast between orality and literacy on these grounds is found in reports of evidence that oral peoples commonly externalize schizoid behavior where literates interiorize it. Literates often manifest tendencies (loss of contact with the environment) by psychic withdrawal into a dreamworld of their own (schizophrenic delusional systematization), oral folk commonly manifest their schizoid tendencies by extreme external confusion, leading often to violent action, including mutilation of self and others. . . "

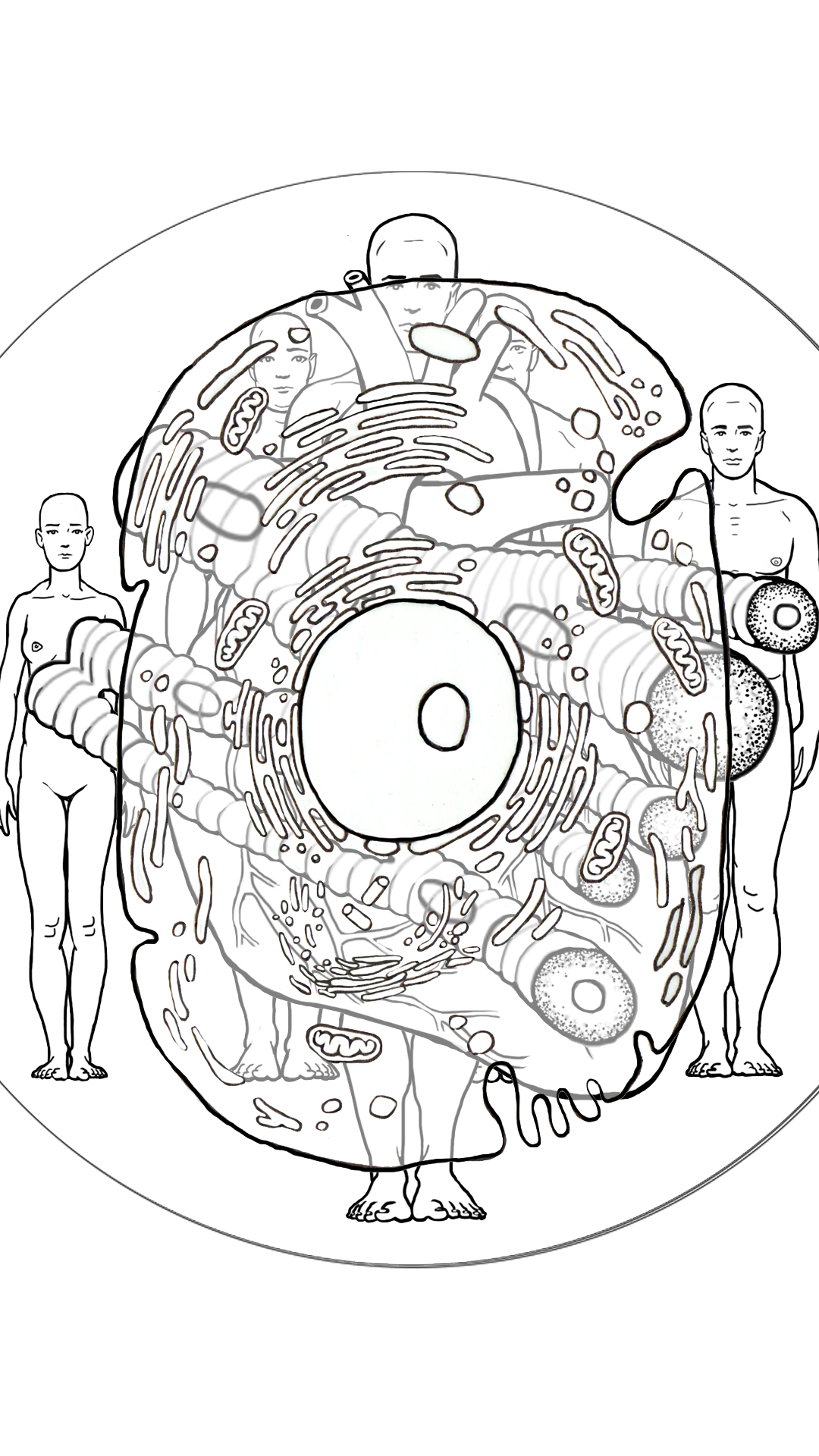

" In a primary oral culture, where the world has its existence only in sound, with no reference whatsoever to any visually perceptible text, and no awareness of even the possibility of such a text, the phenomenology of sound enters deeply into human beings' feel for existence, as processed by the spoken word. For the way in which the word is experienced is always momentous in psychic life. The centering action of sound (the field of sound is not spread out before me but is all around me) affects man's sense of the cosmos. For oral cultures, the cosmos is an ongoing event with man at its center. Man is *umbilicus mundi*, the navel of the world. Only after print and the extensive experience with maps that print implemented would human beings, when they thought about the cosmos or universe or 'world', think primarily of something laid out before their eyes, as in a modern printed atlas, a vast surface or assemblage of surfaces (vision presents surfaces) ready to be 'explored'. The ancient oral world knew few 'explorers', though it did know many itinerants, travelers, voyagers, adventurers, and pilgrims.

Most of the characteristics of orally based thought and expression discussed earlier in this chapter relate intimately to the unifying, centralizing, interiorizing economy of sound as perceived by human beings. A sound-dominated verbal economy is consonant with aggregative (harmonizing) tendencies rather than with analytic, dissecting tendencies (which would come with the inscribed, visualized world : vision is a dissecting sense). It is consonant also with the conservative holism (the homeostatic present that must be kept intact), with situational thinking (again holistic, with human action at the center) rather than abstract thinking, with a certain humanistic organization of knowledge around the actions of human and anthromorphic beings, interiorized persons, rather than around impersonal things.

The denominators used here to describe the primary oral world will be useful again later to describe what happened to human consciousness when writing and print reduced the oral-aural world to a world of visualized pages. "

" . . .Thought is nested in speech, not in texts, all of which have their meanings through reference of the visible symbol of the world of sound. What the reader is seeing on this page are not real words but coded symbols whereby a properly informed human being can evoke in his or her consciousness real words, in actual or imagined sound. It is impossible for script to be more than marks on a surface unless it used by a conscious human being as a cue to sounded words, real or imagined, directly or indirectly.

Chirographic and typographic folk find it convincing to think of the word, essentially a sound, as a 'sign' because 'sign' refers primarily to something visually apprehended. *Signum*, which furnished us with the word 'sign', meant the standard that a unit of of the Roman army carried aloft for visual identification-- etymologically, the 'object one follows'. Though the Romans knew the alphabet, this *signum* was not a lettered word but some kind of pictorial design or image, such as an eagle, for example.

The feeling for letter names as labels or tags was long in establishing itself, for primary orality lingered in residue, as will be seen, centuries after the invention of writing and even of print. As late as the European Renaissance, quite literate alchemists using labels for their vials and boxes tended to put on the labels not a written name, but iconographic signs, such as various signs of the zodiac, and shopkeepers identified their shops not with lettered words, but with iconographic symbols. . .Names were still words that moved through time : these quiescent, unspoken, symbols were something else again. They were 'signs', as words were not. "

( writing restructures consciousness )

" Plato thought of writing as an external, alien technology, as many people today think of the computer. Because we have by today so deeply interiorized writing, made it so much a part of ourselves, as Plato's age had not yet made it fully a part of itself, we find it difficult to consider writing to be a technology as we commonly assume printing and the computer to be. Yet writing (and especially alphabetic writing) is a technology, calling for the use of tools and other equipment : styli or brushes or pens, carefully prepared surfaces such as paper, animal skins, strips of wood, as well as inks or paints, and much more. Writing is in a way the most drastic of the three technologies. It initiated what print and computers only continue, the reduction of dynamic sound to quiescent space, the separation of the word from the living present, where alone spoken words can exist.

By contrast to with natural, oral speech, writing is completely artificial. There is no way to write 'naturally'. Oral speech is fully natural to human beings in the sense that every human being in every culture who is not physiologically or psychologically impaired learns to talk. Talk implements conscious life but it wells up into consciousness out of unconscious depths, though of course with the conscious as well as the unconscious co-operation of society. Grammar rules live in the unconscious in the sense that you can know to use the rules and even how to set up new rules without being able to state what they are.

Writing or script differs as such from speech in that it does not inevitably well up out of the unconscious. The process of putting spoken language into writing is governed by consciously contrived, articulable rules. . .

. . .To say writing is artificial is not to condemn it but to praise it. Like other artificial creations and indeed more than any other, it is utterly invaluable and indeed essential for the realization of fuller, interior, human potentials. Technologies are not mere exterior aids but also interior transformations of consciousness, and never more than when they affect the word. Such transformations can be uplifting. Writing heightens consciousness. Alienation from a natural milieu can be good for us and indeed is in many ways essential for full human life. To live and to understand fully, we need not only proximity but also distance. This writing provides for consciousness as nothing else does. "